October was a big month for Adobe. It has been for the last twenty years, it’s that time in the calendar when it previews all the new stuff and teases things to come. It’s just that this year the hype seems to have been notched up considerably. Make no mistake, Adobe is under pressure. The established industry giant has the new kids on the block trying to kick the door down. And the cause of all this, of course, is Artificial Intelligence. For most of the last two decades big A has been able to stride forward confident that it held all the important cards in digital imaging, illustration and design. But that dominance has been shaken by recent technological advances, so this year Adobe MAX (nothing to do with fizzy drink) had an extra feel of urgency amid all the glossy presentations.

In this cyber world it is at least reassuring that Adobe feels the need to address a live audience in a theatre rather than at arm’s length online, but by its very nature, the massed guests are rather partisan. No chance of heckling here among the faithful. As a result the gathering takes on an atmosphere somewhere between a religious revival and an American election rally - at least without the silly hats and moronic placards. Although they might have been forgiven for introducing a little Trump-style let’s Make Adobe Great Again in the headlines.

You can view any or all of the day's content online if you can bear to put up with the adrenaline fuelled presentations on stage and theatrical reactions from the seats. Alternatively you can find the parts that interest you in numerous more palatable slices if you care to wade through the obvious promotional fog that search engines now create.

The dilemma for Adobe is that despite its global reach, it is vulnerable to the so called lone wolf - some geeky teenager in a back bedroom who will stumble upon an algorithm that will stand the world on its head. Traditionally it relied on spotting these developers and snapping them up so their talents were used for the benefit of the whole company, and the many programmes that spawned from the original digital editing creation. Now there are plenty of speculators who will throw funds at something that looks promising even if they don’t understand it in the hope that it might just be the Holy Grail.

Adobe’s approach, but its nature, is more measured, fuelling AI with its own resource of licenced stock images rather than as some others, and most of our customers do, plundering the internet. This policy is described as ethical but it is equally pragmatic as no one is likely to sue Aunty Mary for that nice picture of a kitten she found for a birthday card, but Adobe is too rich a target to ignore.

One of the interesting snippets I picked up on was that while up until now the generative fill library has been free to use, from November there will be a credits system on image usage similar to that with Adobe Stock.

Of course, not much of this will be relevant to us in the print business but 2024 does have some very useful updates for those of us using Photoshop as a daily tool. In order to find them you may have to fast forward through numerous ‘what’s new’ tutorials to get to the important bits. In fact you can almost judge the value of the video by the priority given to some of the new features.

One which seems to take the lead in many, and can often occupy half the lecture, is called lens blur. Why it grabs so much attention is a puzzle as there have been several ways of softening unwanted detail in the background for years. But it had also been greeted with a certain amount of scorn and derision as proper photographers have been doing this in camera for over a century. The fact that a computer can now do it when it has access to detailed information about the lens and capture settings is hardly ground breaking. If your tutorial majors with this gimmick, to coin a phrase, move along please, nothing to see here…

Like many overblown features of AI, it is simply part of a trend characterised by something else I picked up on from one of the Adobe MAX sermons - the democratisation of creativity. Now what does that actually mean -that anyone can be a Van Gogh or a Beethoven? We already live in a media world where any non-entity can be a celebrity, or worse an ‘influencer’. But to be truly creative I think you do need some element of talent, or am I just old and cynical? I will let you decide, but I’m sure you already suffer from customers who think they are an artistic genius. Looks like more are coming, empowered by AI.

But it’s not all bad news, underneath the gloss and glitter there is some real gold. Two outstanding features have been added which really will be a big boost to improving print workflow, and they are much more useful that any eye-catching gizmo.

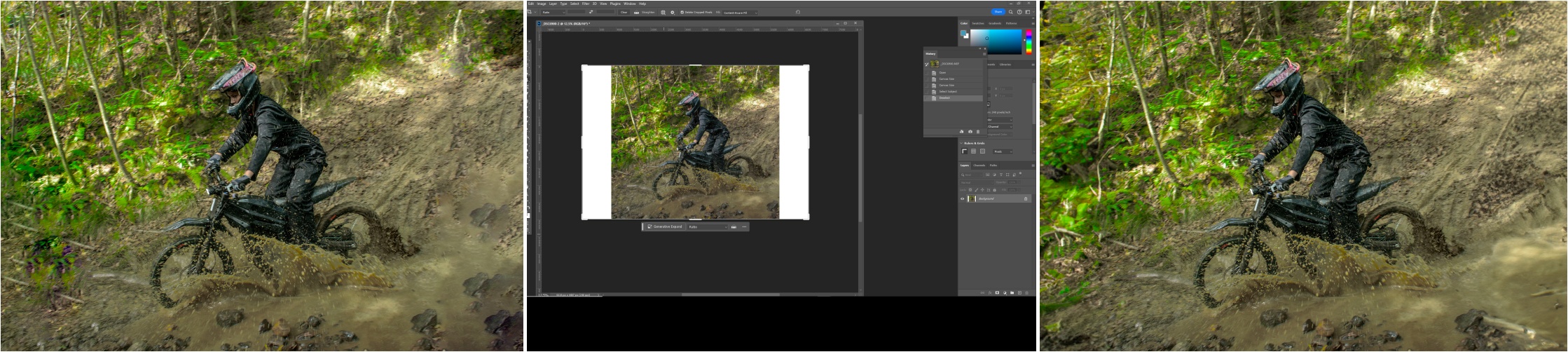

Generative Expand - not fill - addresses a daily task in changing the size and shape of an image to fit the size of a print, whether simply to add bleed around the edges, or physically change its dimensions and orientation - portrait into landscape for example. If it’s just a solid colour that’s required, it’s not a problem. More recently Content Aware became a handy tool for creating those extra inches. But even with manual control over the sample zone, Content Aware can be a little unpredictable, and worse if you use the crop tool to expand the canvas size and use that function without manual supervision.

Generative Expand uses the crop tool in the same way to extend the bounds of the image, but using a smart generation of AI can create a much more realistic panorama, less prone to repetition and random pixels. You can see the dramatic difference between the two in the picture of the trials bike going through a mud splash which starts out square to suit social media, but then is extended to more of a landscape to fill a space. With Content Aware, rocks and tree trunks have been obviously cloned and thrown into the mix whereas GenEx does a pretty good job of creating a whole new but complimentary larger landscape.

As ever, the cautionary note is that it’s not going to be perfect with every image. How it interprets the content will depend on what it is given, and that is still down to the judgement of a processor rather than human intuition. So keep the manual override options always to hand if you need to take a step backwards.

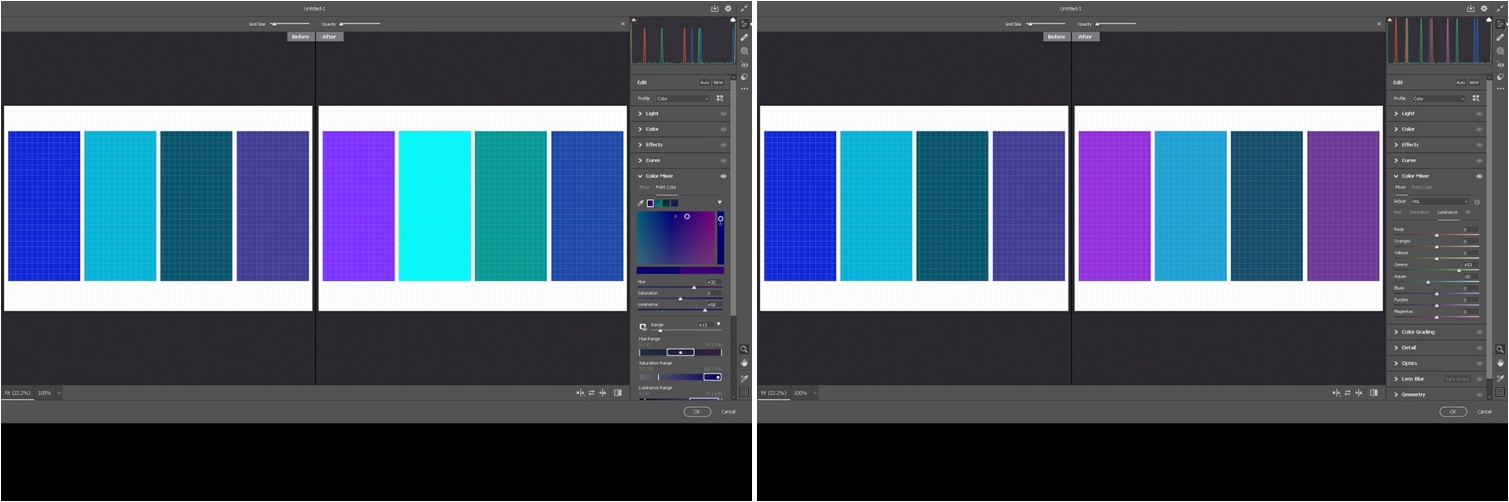

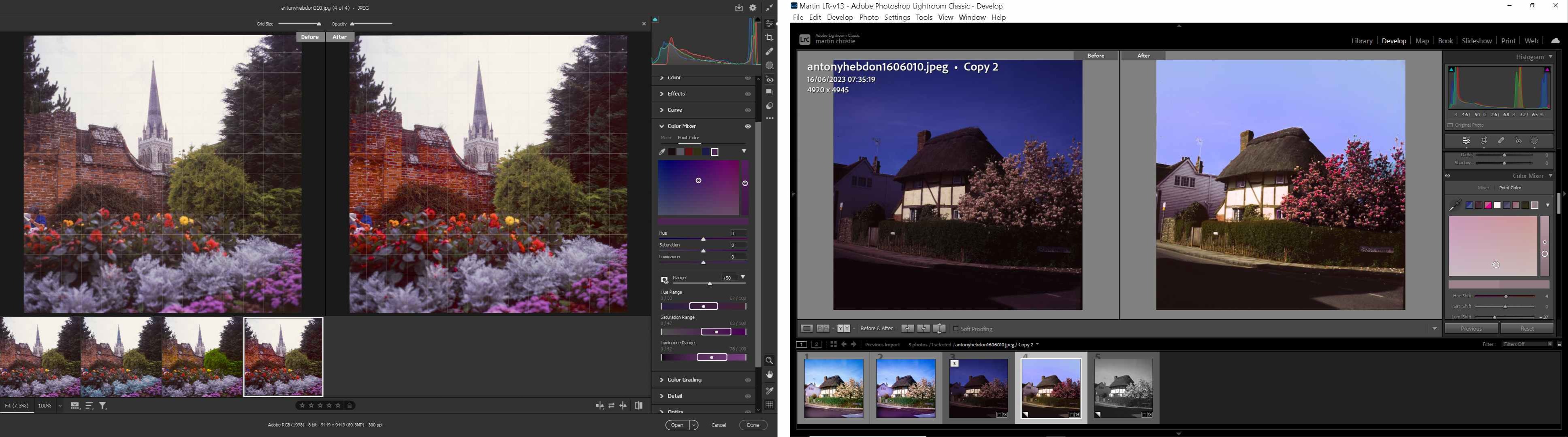

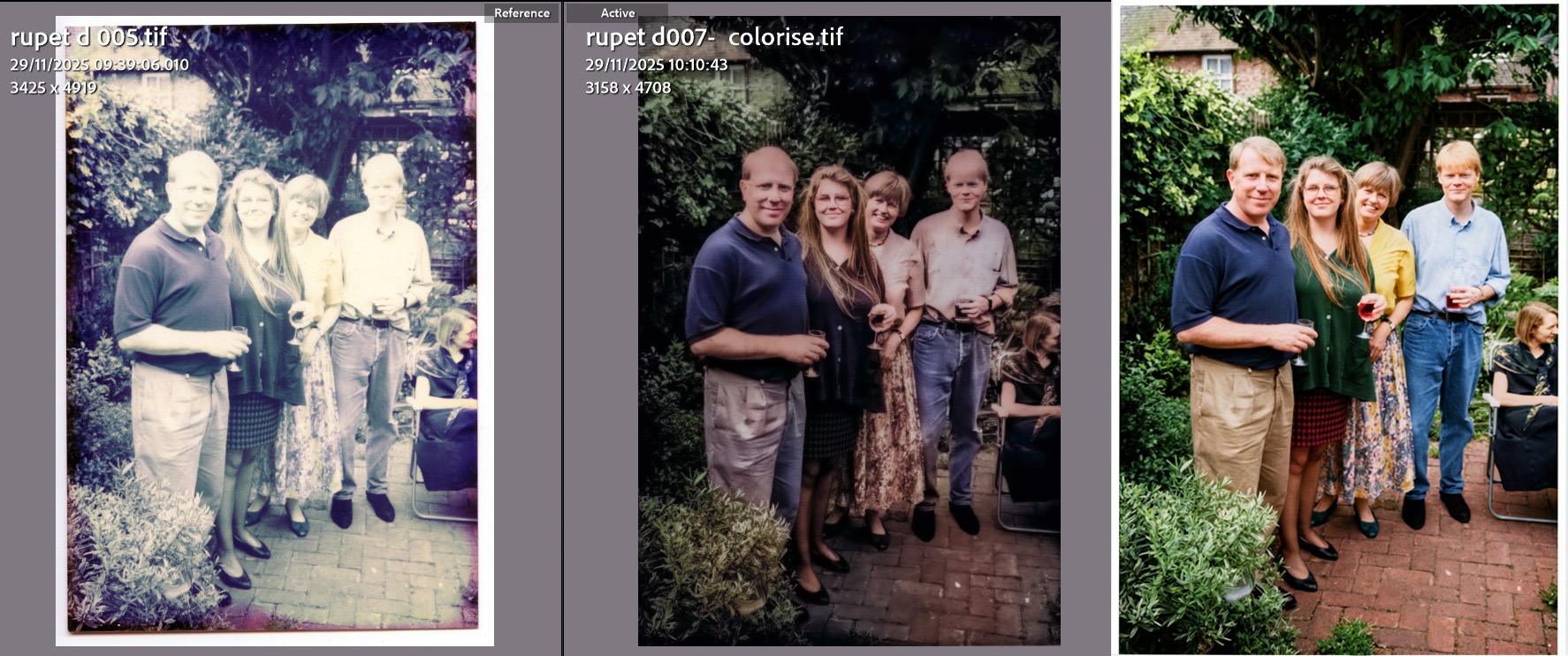

My new favourite tool however is the Colour Picker. This has all the electronic assistance but with full human control. Last month I illustrated how I brought an old colour transparency back to life using the masking tool and colour adjustment to enhance some of the elements in the picture. This new tool does a similar job, but makes the task even easier.

The advantage of the Colour Mixer is that rather than the simple control of CMYK or RGB, the Mixer has eight colours adding Orange, Green, Aqua and Purple to the available gamut, and each of these can be adjusted in three different ways, by Hue, which is the actual colour, Saturation, the amount of that colour, and Luminance which is the intensity of the colour emitted from it and often the most important for print.

This was already a game changer for me as I do a lot of artist Fine art prints that have been scanned or photographed and however well they have been turned into digital content there is always some corner of the colour range that is just tantalisingly out of reach with ink and paper. While the Colour Mixer gave me a lot of control of output, unless I used the masking tool, the effects were spread across the whole image to one degree or another. You might get the blue of the sky right, but any cyan content in other places would just have slipped away.

The Colour Picker is like a smart missile targeting exactly the right spot, and having the same adjustments of hue, saturation and luminance, as well as range control so you can further define how far you want the colour reach to go. In the example of the four blue strips you can see the difference between the two - you can adjust the individually blues without changing any of the others. Simple.

The caution is that it is simple if you have a perfect file to work with. Unfortunately so much of what we have to deal with is so much less than perfect and the limitation of all of this technology as ever is the input. If you’ve got lots of pixels, you’ve got lots of colour information you can play with and it makes it a lot easier for the techy side to do its magic.

Without enough of those little squares and even the smartest artificial brain is going to struggle. It will always produce something - it has to. But it won’t always be what you want or expect. Certainly it probably won’t be what the customer expects, which is why you need all the help that Adobe can provide.

There are likely to be a few more things I have yet to discover, things certainly more useful to the professional than Lens Blur, so I will keep you posted as I find them.

.jpg)

.png)