We left 2025 with a bit of a cliff hanger tipping on the edge of a whole new working environment influenced if not dominated by AI. Artificial Intelligence of course is the buzz word of this quarter of the 21st century to the extent that you can’t seem to launch any product without attaching it as a prefix or suffix at the risk of appearing outdated if not completely redundant.

It has always been so. Once upon a time the name digital promised progress and modernity long before it became tainted as something that couldn’t be repaired or updated when the software passed its sell by date.

Any advance in technology has equal measures of benefit and cost - often only realised in the long rather than the short term. At the moment opinions seem to be equally divided.

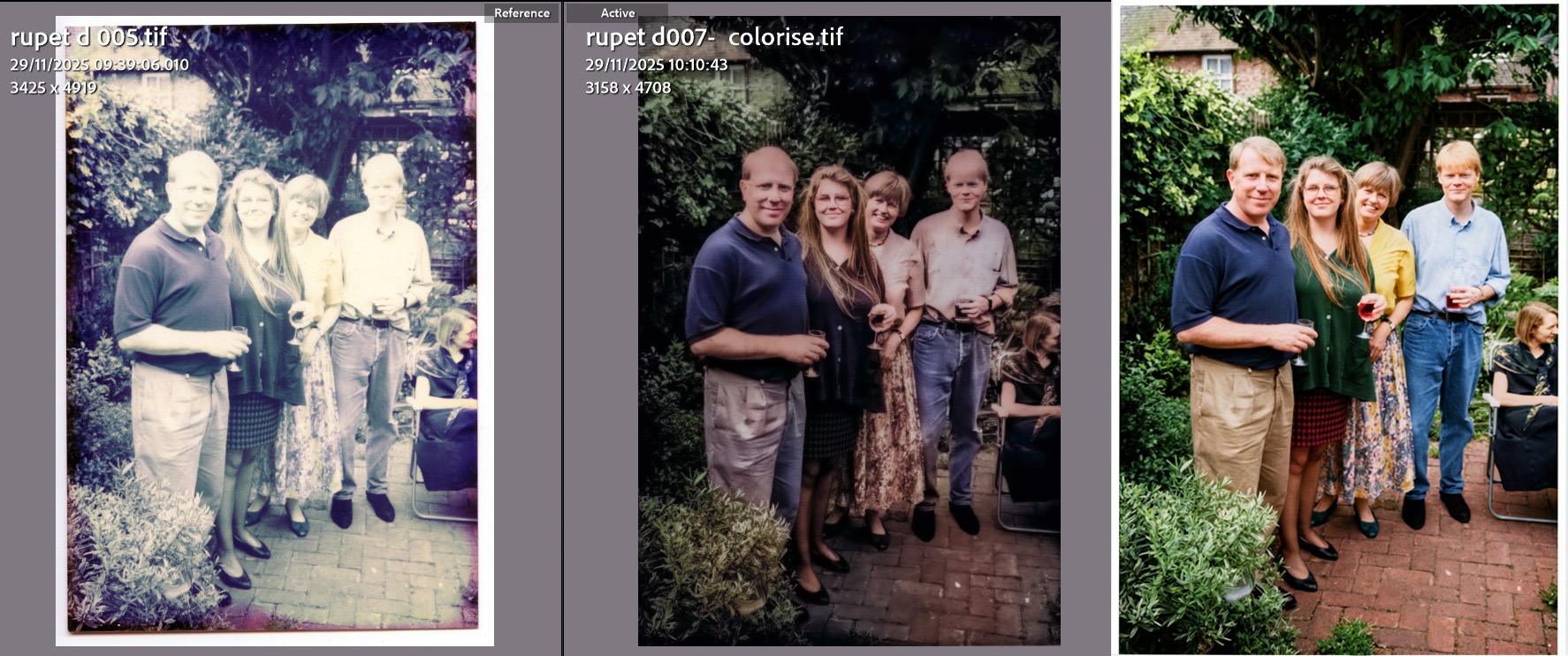

Personally my position is similarly both positive and negative. As a photographer I took on the challenge of digital without rejecting the appreciation of traditional film. That progress led me to get more involved with printing than simply dabbling in the darkroom. From desktop to large format the inkjet process created a much closer understanding of how electronic imaging translated colour and detail, giving me not only a second career in direct print, but a much greater knowledge of how a modern camera interpreted the world.

And that last effect is important as my relationship with film - despite 25 years working with it - has never been to consider it magical in itself as many still do. It was always an optical mirage turned into reality by a chemical reaction. Any magic was in the eye of the individual photographer to use that stored potential into something special, and often something quite unique not seen immediately by the naked eye.

Back in the days of film proper photographers were few and far between. Even enthusiastic amateurs would only shoot a few dozen rolls a year - hardly a couple of hundred images in total. That was the practical and affordable limit of the technology of the day. This meant a steep learning curve to reach professional or creative standards simply because it needed time behind the viewfinder to achieve results beyond a lucky one off.

The early days of digital were perplexing as no one had any previous experience, and although so many more people were able to capture images, the shared experiences only seemed to confirm that the process was much more random and unpredictable. It was convenient, but chaotic in its output. This is why some simply condemned it as a novelty, and others new to the system simply gave up as it couldn’t reproduce the magic wand effect that had been promised.

This was all very unfair as in comparison film had had over 150 years of development and I’m sure the early Victorian experiments suffered just as many frustrating failures trying to make sense of the mysterious method of image transfer. The major difference is that once the process had been more or less understood, and the materials perfected, any improvements were mostly incremental. Film could last for years long after its sell by date and mechanical cameras, like my 40 year old Nikon, were still perfectly serviceable, with or without batteries.

Digital devices, on the other hand, and the software that goes with them date very rapidly as we have learned to our cost. That is in the nature of the technology which expands exponentially - that is in every direction all at the same time like some expanding universe. AI in this context is just another big bang along the way, not the final solution. It’s a process, not a product, and love it or loathe it that process will progress relentlessly in the background of many of the things we work with.

That is why it is important to have at least a basic understanding of how it works to understand or possibly anticipate some of the unexpected consequences that may arise. AI is not just a faster computer programme, it’s a smarter way of exploiting a much greater amount of digital information than previously possible, to achieve unprecedented results. But the unexpected element is itself the possible flaw in the process. Almost everyone wants things faster, and better. But be careful what you wish for, as they say.

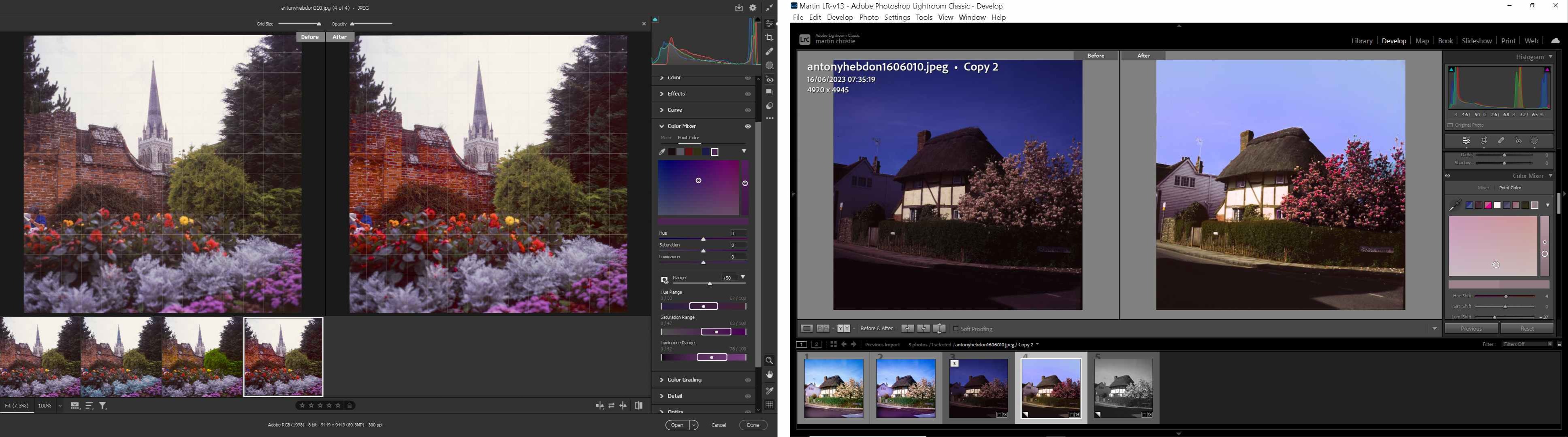

As a long term Photoshop user I have, in some small way, been helping Adobe develop its own AI over the last decade so I guess I’m partly responsible for wanting tools that transformed images so much better than the painful manual operations of years gone by. Compared to some of the early versions, the modern PS control panel is as different from that of a 1920s Model T Ford to a modern Formula One car. It still steers the vehicle, but the computing calculations, and the possibilities, are beyond comparison.

I often use the example of driving as it’s something that demands a significant amount of essential human skills - direction, anticipation and control - over a machine. Even those promoting driverless vehicles, with computer sensors in control of these actions, accept that there may be times of crisis or uncertainty when a human has to intervene. But that is precisely the reason for caution over an entirely autonomous process as how is a person, increasingly detached from learning practical solutions, prepared for the unexpected?

Serendipity is that discovery of something valuable by chance rather than expectation, and is part of very human learning and the accumulation of experience. A chance discovery remembered may later trigger a lightbulb event to provide a solution. Our brain cells are capable of thinking outside of the box. I’m not sure whether AI, or at least the way it is being employed, is quite as flexible. Hopefully I’ll be proved wrong but it does seem that many of those championing it as a one stop solution have limited experience of using it, or have not explored possible alternatives.

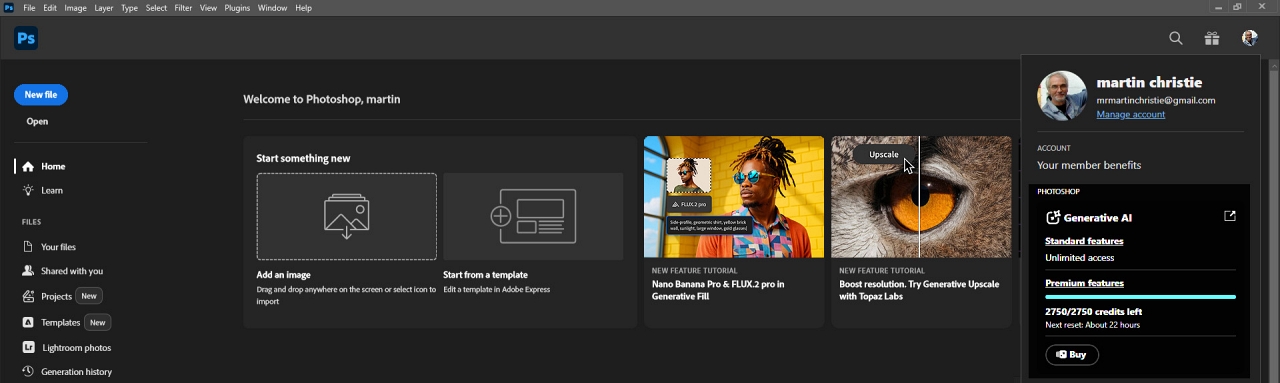

The last option is very much the case with Photoshop because unlike some much promoted alternatives that have gone full blown artificial creation, Adobe still gives you choices. And there’s a very good reason for this as along with many major updates from last year, you may now have generative credits docked from your account. This may have slipped under the radar of many users as the marketing hype of all the new features didn’t actually point out that you would have to pay for some of them - as part of your current subscription fee.

Most importantly, some of them cost a lot more than others, and while that has a certain logic as it is related to the computing power involved, it doesn’t necessarily reflect the quality or accuracy of the result. So it isn’t actually a case of you get what you pay for - in some cases you don’t have a choice. Even if you don’t like it you don’t get your credits back.

You are probably already aware that for some time you have had the option of using so called cloud based computing on line rather than your own processor. This is because Adobe’s data banks have much greater resources than your average desktop, but calling upon them may make you liable to additional charges. It’s a matter of checking the hidden detail and it’s not entirely clear cut.

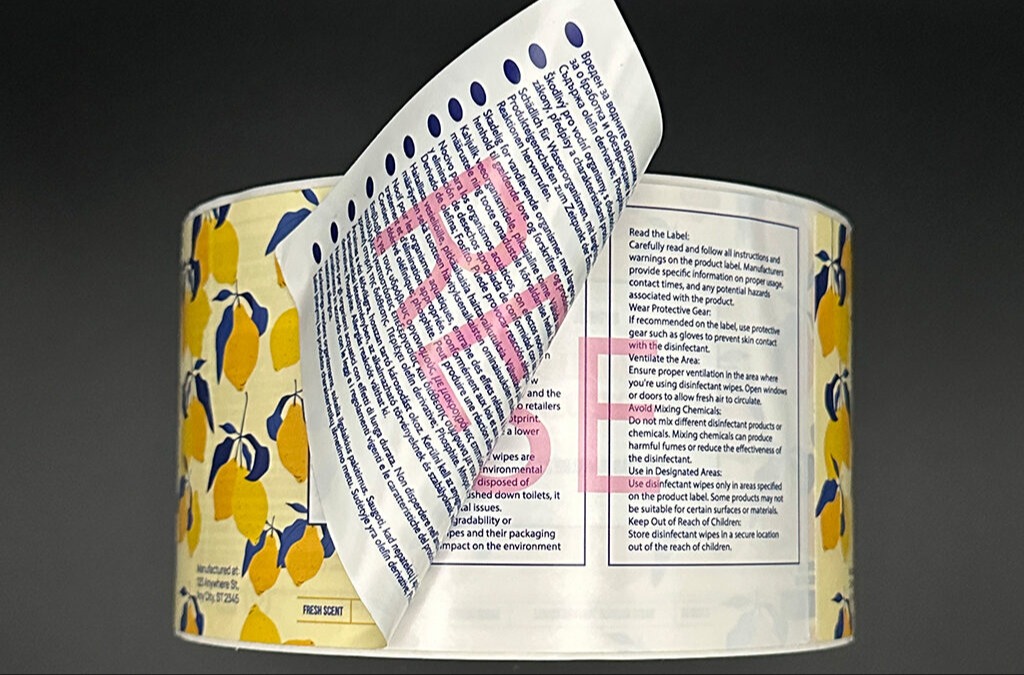

A good number of AI features that have been established in PS over recent years like Content Aware, Selection Masks and the like, do not use any credits. This is because they are essentially sampling existing pixels and reassembling them. When an action starts with the word Generative however, this is where the penalty clause may kick in because you are asking AI to create something entirely new, even if it’s actually based on something that already exists. Confused? Well there’s more because Adobe has recently added some partner programmes from already established AI platforms.

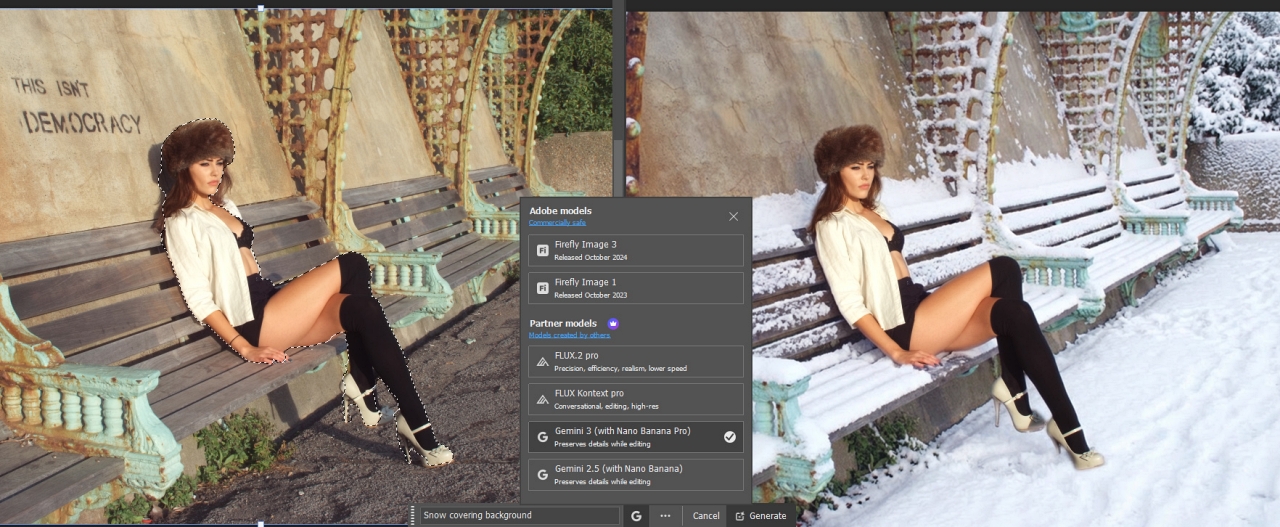

Their own Firefly versions, developed from 2023, have been supplemented with Flux and Gemini with Nano Banano. Even they have variations, and I have no idea who thinks of the names when a more descriptive choice might be more appropriate. You can find all these options in the contextual task bar when you make a selection. But you have to dig deeper to find out the price tag, and that’s the rub, because there’s no guarantee that a higher debit count will produce commensurate results. In fact the opposite may well be the case as relying on machine imagination has often hilarious results.

The output will depend on the input and as I can’t cover every possible scenario here. I can point you to a couple of excellent visual guides online below. You can switch the AI assistant off altogether, or even have it on auto pilot so it may use it only at its own discretion. And it may be that having a couple of thousand credits at your disposal a couple of extra won’t be a loss - but some actions may use 40 times that. When some users increasingly turn to AI as first call rather than last, this can build up to be an issue if that choice has to be repeated many times to achieve a goal.

You can buy new credits if you use up the existing ones already in your account and that depends on the Creative Cloud plan you have. You need to check your balance by going into your profile on the app and that will give you a monthly breakdown.

And it’s worth monitoring your usage just to see how much you are dependent upon them rather than any alternative. The catch is, they don’t roll over like a savings account. They reset every month so it’s use them or lose them. You won’t have any in the bank if you get a busy month.

Generative credits are applicable in both Photoshop in Lightroom so it is worth getting abreast of them especially as there are other tools available in both which don’t use them and may do a better job with more human insight.

It might also just make a tiny difference to the growing burden of industrial scale data transfer worldwide.

Aaron Nace has a really useful podcast

https://youtu.be/O1PgSiEdQAg?si=j_8FOOS5yRjErSoR

How to find your Adobe credit score

https://youtu.be/zcw_vdqDOA4?si=myOXx1P83TmvBKHA

And for the alternative voice on everything AI my favourite Aussie

https://youtu.be/N7BBTk5lXxg?si=_LPAc3qywhz1VVRA

In the interest of balance here is Adobe's point of view

https://youtu.be/wulN5I95qwg?si=jNFxVQMyUywxfmsl

.jpg)