Of course you don’t. It’s just the kind of strap line that’s all too familiar in popular use to entice you into spending time browsing something you would probably choose to ignore if you had more information. Even a few precious seconds lingering just to see if it’s of interest is sufficient to be of benefit to someone - generally financially. It may only be a fraction of a penny but multiplied by millions the numbers add up.

I’m sure we all know this and are resigned to it as just part of modern life, but it has a more insidious effect on the way we receive news and information. These seductive introductions are increasingly created by artificial intelligence which learns and mimics the sort of messages that are likely to grab our attention. It has learnt that the more outrageous and ridiculous the claim, the more attention it is likely to grab.

Older readers may recall that I started my professional life as a journalist in the days of hard copy. And although it would be fair to say that even back then newspapers would indulge in a fair amount of headline grabbing, apart from a few notorious tabloids, most quality publications were aware that if they continually hoaxed their readers with false claims they would lose them.

I was trained to put an outline of any story in the first paragraph - enough for a reader to judge whether it was worth continuing to absorb the finer detail. This was then read by the Sub-Editor - a more senior post - who would ultimately compose a suitable headline to direct readers to the content. In the structure of the content it was important to leave nothing to the end that could not be cut out if it needed editing to make room for a bigger news item - hence the catchphrase ‘drop the dead donkey’.

This produced a discipline of framing a story that could be summarised as quickly as possible rather than the opposite, which is why I am comparing it to the AI approach which will become relevant shortly.

We are increasingly seeing machine learning moulding not only the headlines, but the content, even of our emails, which can have fundamental implications on not just how we communicate but what we communicate. This of course may be all well intentioned to avoid us wasting precious time sifting through useless reams of chaff, but it is also equally responsible for creating it.

Human beings are easily distracted and not great at concentrating on the details. That’s how magicians get away with the simple trick called the French Drop. where they swap a coin from one hand to another and the viewer is too busy following the movement, not the target.

At the end of October the annual Adobe MAX conference launched in Los Angeles and no doubt produced a lot of processed headline news about a lot of AI innovation and while it’s unfortunate that it’s too close to deadline to review in this column, it does give me a month to study the full detail and find out the facts that are relevant to us in the print industry hidden beneath the inevitable marketing gloss

Adobe has been forced into the escalating hype by the claims of others climbing onto the AI bandwagon in recent years, with even more specular claims for its products. At the same time there have been plenty of social media threads along the lines that it was all over for Big A and that subscribers were abandoning the Creative Cloud in droves for cheaper or better alternatives. Of course there was no shortage of sponsored podcasts promoting these.

I recently did a very brief look at some of these alternatives and concluded that while there were certainly options for the personal user, for the professional requiring multitasking at their fingertips, the CC was still by far the most comprehensive collection currently available. The one question was whether you might need all of the suite on all of the studio computers or whether a pick and mix policy might suffice.

One of the reasons is that while not all of customer content arrives actually print ready, the prevalence of user-friendly editing and design software - ironically due to that very AI - means that much of it no longer needs the amount of technical adjustment it once required.

One of those easy fix solutions is actually contained within the Adobe stable and I have to confess Adobe Express had rather gone below my radar as previous one stop options provided had proved disappointing. Newer users, less biased, and versed in the instant media world for which it was designed, have made me think again. If you are already using it this is not news, but for any less educated like me, I will include a review of its possibilities in next month's issue. Certainly much more than a tool for doing eye-catching reels on Instagram.

My personal preference for an Adobe alternative has been Affinity which has a photo, design and publish option - or at least has had up to now. In a rather strange global move online sales of the software were recently halted and the website frozen. Hopefully this is just a precursor to the launch of Version 3 but the melodramatic hiatus has caused a flurry of speculation on the web with very few pundits having a favourable view of parent company Canva who purchased the much smaller one last year.

Australian based giant Canva has very much captured the general public market as a result of its free option for mobiles, and would dearly love to topple Adobe in the professional stakes. In a few days, news will be released so if you go on the Affinity website you will know as soon as I do.

It would be a negative step if global aspiration strangled creative talent but we shall see. Big corporations don’t have a great track record.

To some degree design is straightforward - fitting content into specific dimensions. So it’s relatively easy for AI to sort out square pegs and round holes. Digital imaging however has always been problematic which is why this column was requested to have a presence in these pages in the first place when it was still a novelty.

Digital cameras came long before smart phones so those of us transitioning from film had time to get our heads - and particularly eyes - around the new technology. In 35mm days it was important to understand what the camera saw in terms of colour and detail because you didn’t have the luxury of reviewing it until much later. It still is important but few people realise it because it is so easy to simply capture any old image and assume that it’s real and not an illusion.

Digital devices don’t just capture an image - their processors interpret it. Even the barely processed RAW files which I now almost always use require at least some point of reference to allow some electronic calibration which can be manually adjusted on the monitor in post production so I still have to make some mental calculations in my camera settings. For most people it’s just point and shoot. But of course there’s a direct relationship between making something convenient and making it understandable.

With customers we have an invaluable source of example of the yin and yang of this process with two perfect ones just this very week.

The first involves some pieces of art photographed by a person - I’m not describing him as an artist as that is rather more a personal title than a qualification. I work with a number of very good creatives and most of them have an excellent understanding of the nature of colour so we can have a useful dialogue on digital reproduction. In this case however there was no discussion. The photographs had been taken on a phone, and entirely on automatic settings. I had no reference to the originals, only the digital files supplied. Out of five files, four were perfect, but the fifth was way too dark and had ‘too much black’ and the customer wanted a reprint or a refund. He actually brought in the original canvas expecting me to match his original free of charge.

I pointed out that all five files were printed at the same time on the same printer, on the same paper so that any issue had to be the individual file, the content of which was being decided by his phone, not my printer profile.

He wouldn’t accept it and went off with his original under his arm saying he would go somewhere else and I wished him well knowing most local printers send troublesome jobs to me!

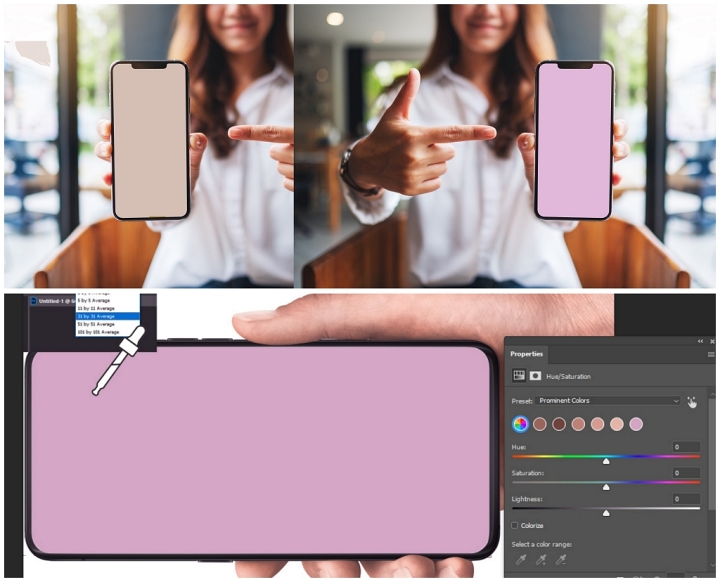

The second example being the exact opposite - a customer asking my expertise on matching a product colour to create a background for social media postings. I’d been sent a phone snap of one of the box tops and it appeared to be beige - one of those colours that immediately rings warning bells when it comes to the possible variance of composite printing. So I asked to see an original item rather than a digital copy and it turns out if was actually pink. So rather than wasting a lot of time trying to match a non -existent hue - hands up how many times you have done that - it was possible to do a decent reference can and work from that so at least we started on the right side of the colour chart.

As well as being the right colour, the background also needed to be a shade lighter so that anything in the foreground stood out better - logical as anything further away from the subject will generally appear darker. In order to be accurate the only option is to do a simple test print and work from that. A monitor screen, after all, is a composite of RGB pixels, not solid colour, as well as being backlit. In print is the real thing.

The colour picker tool has been around in Photoshop of a long time but many users don’t know that you can adjust the pointer to take in a wider sample zone - effectively taking an average of a number of pixels. This can better reflect the actual result colour than one possibly unique one. You can widen the search area from one to one hundred pixels radius.

The colour picker tool has been around in Photoshop of a long time but many users don’t know that you can adjust the pointer to take in a wider sample zone - effectively taking an average of a number of pixels. This can better reflect the actual result colour than one possibly unique one. You can widen the search area from one to one hundred pixels radius.

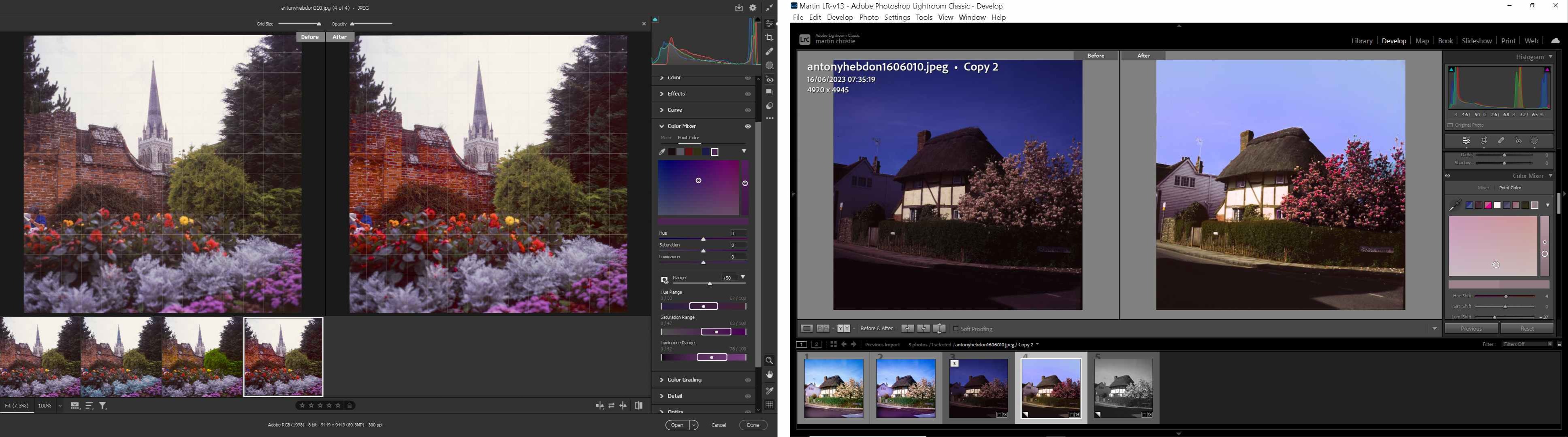

Alternatively you can use the new Adjust Colour option in the Contextual task bar I have illustrated in previous columns. This works slightly differently, instead of simply taking a dab at colour, by using AI to identify the six prominent ones in the image. The sampler in this tool will show you the area covered by the search so you can move it around to perfect your selection.

Or again you can use selection masking to isolate colour in Photoshop or Lightroom but probably more on masks next month as they are likely to feature in Adobe updates coming even if they don’t take centre stage. You can find out long before you read it here.

.jpg)