The giraffe is a remarkable animal. Its long neck, stretched by the evolution of generations has enabled it to reach those tasty morsels at the top of trees out of each of those more vertically challenged beasts. That feature makes it easier to single out from other animal herds on the African plains. A less obvious individual feature is its distinctive markings. These are apparently completely unique to the individual. No two are alike, and apart from the effects of growth, they do not change from birth to death, and enable them, along with sound and smell, to distinguish each other from the crowd.

This is no doubt the case with many species, as a genetic identification, but would only be recognisable to the human eye if the observer were spending a lot of time to become familiar with particular animals. Of course we all know this because we would instantly recognise our own pet cat or dog amongst a pack of similar quadrupeds. The reason I mention the giraffe is because I recently learned that its survival rate was being improved by the application of the remarkable abilities of artificial intelligence. Instead of having to fit tracking devices, which involves stress and risk to the animal, now thousands of digital snapshots can be taken and compared to quickly check migration patterns, survival rates and the like. A process that would have taken weeks or months manually, can now be done in seconds, enabling conservationists to react in real time.

I always enjoy picking up random facts like that because there is often a relevant cross over example in other areas. It occurred to me that AI would make short work of those ‘spot the difference’ picture games that once were very popular on the printed page and would task the daily commuters passing the time on the tube journey into work. On the other hand I think it would find the ‘spot the ball’ competition that used to grace the football pages rather more challenging because it contains a much more random judgement of the trajectory of a spherical object when kicked. If it was always in the predictable place, for example, the goalkeeper would always catch it.

Of course AI would be able to methodically search the pixels to discover which ones had been doctored, but then that really would be taking the fun out of it. Besides a smart picture editor, knowing that, would simply increase the sampling area to obscure the original source. Knowing how AI works, and anticipating its methodology, is the key to making it work for you rather than making you a helpless victim. It will only really help you if you give it a lot of help because you are the only one who knows exactly what you want.

A common task, for example, is piecing together several sections of a larger scanned original so that it produces a seamless copy the original size. This was always done manually on the computer by using layers and exploiting the alternate levels of transparency to line up the parts, or using the Difference mode to match the pixels. Doing it visually, the eye will naturally look for straight lines so you will tend to get those straight bits right first and worry about the fiddly bits later even if you have to use an eraser or clone brush to touch up bits that didn’t quite match.

There was always an issue if the parts were not scanned exactly straight or there was some optical or colour distortion.

Now that Adobe, along with other image softwares, offers us a more sophisticated photomerge it’s important to understand that because of the way it works the ‘fiddly bits’ are just as important as the others that may be more significant. And while it will do an amazing job very quickly with very complicated puzzles, there will be, just now and then, some odd items added where it has just decided to do so.

In order to be safe you just need to give the programme as much help as possible and give it as much accurate information as possible rather than just enough. Instead of scanning an original in two parts, for example, scan it in at least three, so the pieces have a generous amount of overlap. In manual days, having more sections actually made it more difficult or at least more time consuming. For the computer it is just the opposite. Information overload is no problem for an electronic brain because it's not distracted by the visual impact of apparently conflicting items. It can see the wood as well as the trees to use an old analogy.

For a similar reason, it is important to understand the individual parts of a digital image, the pixels, before you wander too far into the wonderland of AI enhancement. The widespread use of the word upscaling, and fanciful images of what miracle could be possible have rather clouded the basic issues and further raised people’s expectations of what is possible.

From the very beginnings of digital capture there were always claims to have created the magic bullet - a tool that would make any pixel picture as big as you like. And ever since there have been miserable disappointments. As a photographer who moved from film I struggled to understand why a 35mm image could be projected onto a giant cinema screen without an apparent lack of quality, but an electronic one could hardly reach A4 size without falling apart.

Eventually I got my head around it but it has been a continuing journey, and the reality is still that however clever the software, it still relies on the quality of the information fed into it.

What has made the difference in recent years is obviously AI and its ability to better extend and replicate pixels rather than just rubber stamp them. There are a number of fairly good programmes now available including on line ones, but they are an extra purchase and often only work one image at a time.

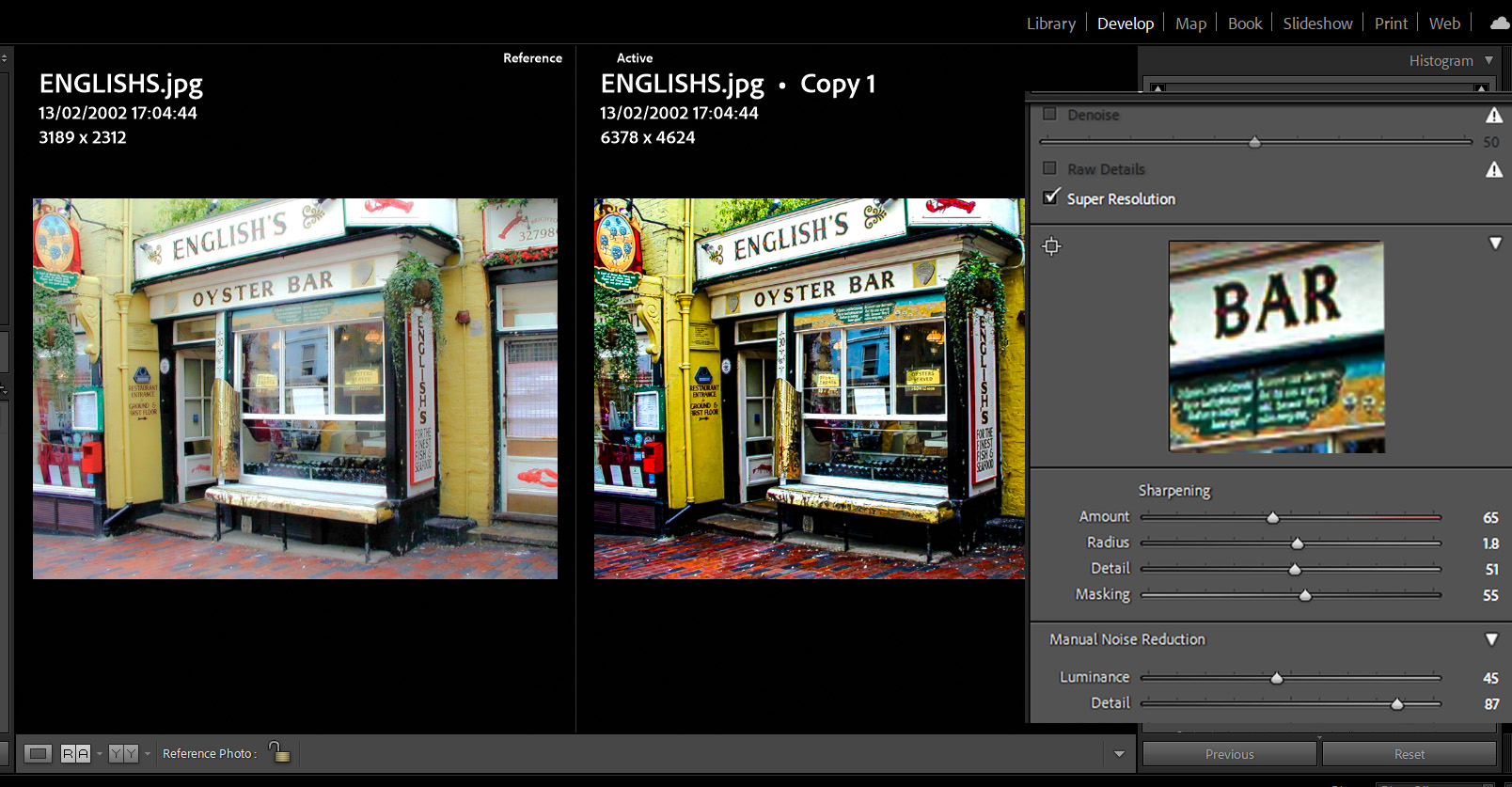

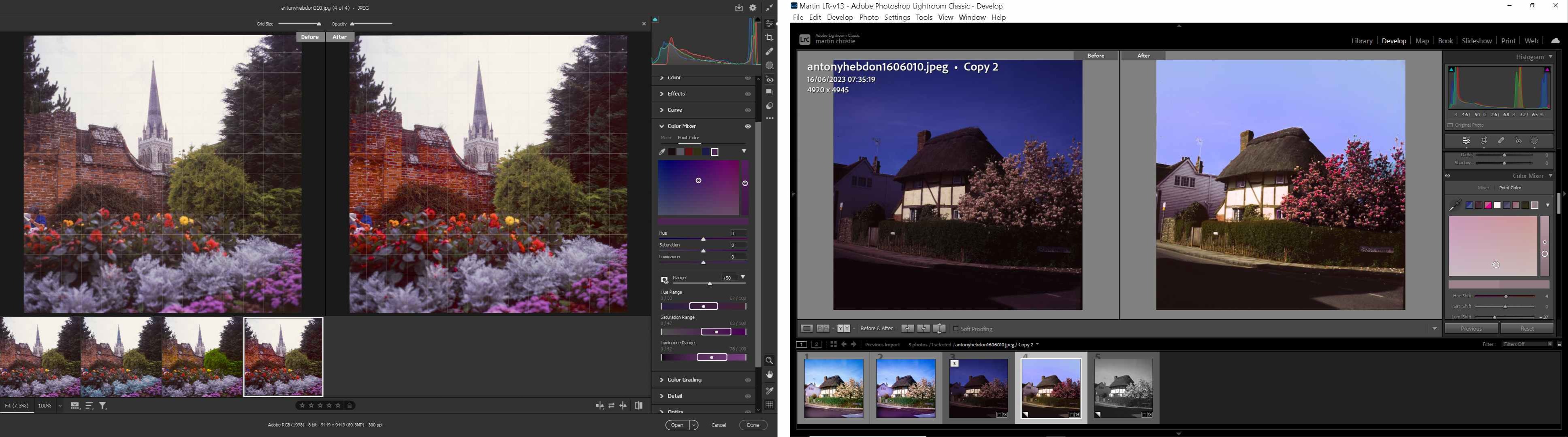

If you have Adobe Lightroom in your package, it now has a new Super Resolution tool that works on most pixel files and can be used on multiple files simultaneously so it’s both fast and in testing extremely good.

My digital camera adventure started more than 20 years ago so I have images going back to when 6mp was top spec even for a DSLR. Frustratingly some of them are quite good except that the quality is poor by modern day standards. The problem has been that trying to enhance them has always proved to be that the result would always either lose sharpness or increase contrast, neither being acceptable, especially with people. So I’m pleasantly surprised to find that the new LR Super Res manages to do a very good restoration job, and I can rattle through old archive folders which I thought were doomed for eternity.

It works best on original files - not ones already edited and already butchered by early attempts in Photoshop which we thought back then were so cool - much like Steps and Westlife to name a few bad ideas that didn’t last the test of time. Unfortunately with badly bruised and hastily saved Jpegs there is no going back. Fortunately when Lightroom was introduced it saved a lot of priceless archives as it spared the originals and only doctored a copy. In the days of film you saved your priceless negatives and only played with the disposal prints. The principle is the same.

So Super Resolution, unlike an original Enhance process, is tucked away in the Develop module alongside a related AI denoise/RAW detail option which is better for files that are already of a higher resolution. Super res doubles the pixels in a linear pattern so a 1000x1000 pixel becomes 2000x2000. It’s as simple as that and it manages to do that without increasing the electrical interference of noise which has been the Achilles heel of similar options so far.

How it does it is far beyond me but safe to say the enlargement processes are starting to compete with the flexibility of film.

So at an A4/A3 level, phone images which are the common source of images these days, can be printed with reasonable quality with a minimum of fuss and saving the awkward moments at the counter when customers study the results from a device they have spent a lot of money on.

They are only ever going to blame your printer, not their original mobile purchase. At the same time small exposure and colour adjustments can be made and synced with a series of similar images. Just do the enlargement first then you’ve got more meat to work with.

Super Res also seems to work really well with low res graphic files - the type you often get attached to flyers and business cards. The customer has long lost the original and recreating it would be costly. Just the doubling of size while retaining integrity can make all the difference in print.

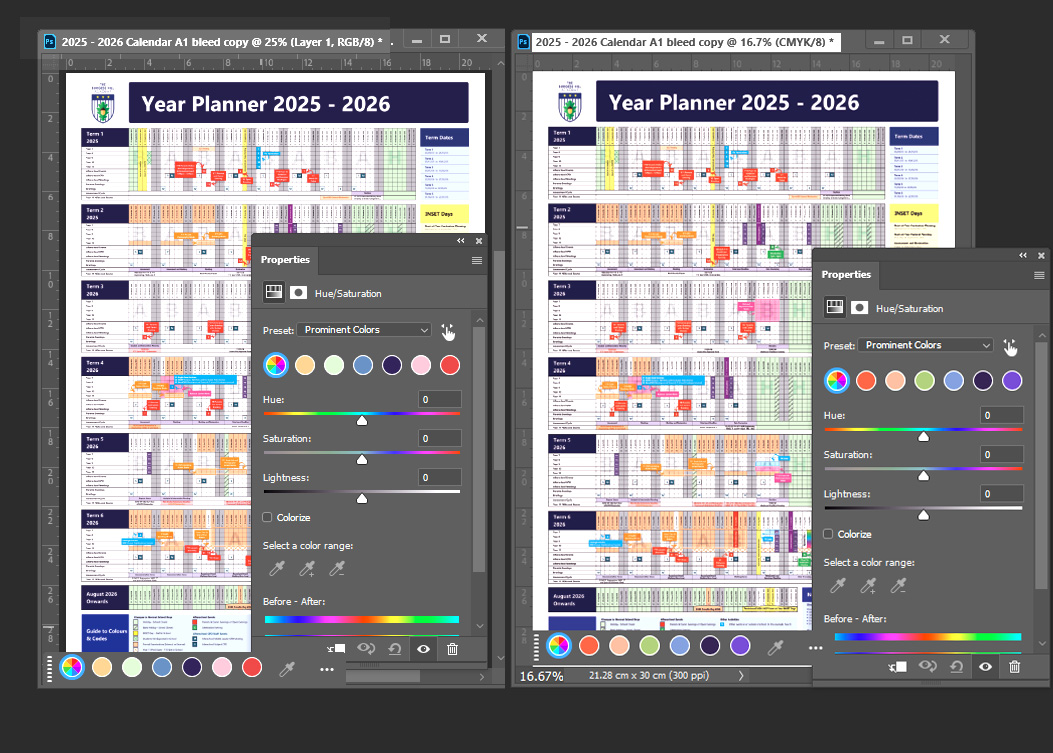

One other new feature I have been praising in recent columns is the Adjust Colour option in the Contextual Task bar. This is where AI is actually an aid to human perception because rather than the sometimes fickle eye deciding colour it decides the six dominant ones in any image and isolates them to adjust. This means even a basic understanding of Photoshop can make fairly important colour corrections for print. More expert users can combine the feature with masks and layers to make really fine tuning possible if the job deserves it.

Something I just discovered about this tool only this month - never even mentioned in Adobe promotion - is that it works in both CMYK and RGB. As I have long recommended wor king in RGB as the native colour space of everything apart from subtractive printing this makes any final conversion much simpler as you can place two images side by side and adjust particular colours accordingly.

king in RGB as the native colour space of everything apart from subtractive printing this makes any final conversion much simpler as you can place two images side by side and adjust particular colours accordingly.

As I have often complained, as printers, we have been rather forgotten in the rush to promote purely visual media, so it’s no surprise to me that our boxes don’t often get ticked by the marketing department. But the bonus balls are there even if you have to dig deep to find them under the promotional gloss so I will try and keep finding them for you.

.jpg)